Supporting imagery

A quick introduction

A console often summarised by its short lifespan and limited colour space. While technically correct, I believe these attributes tend to overlook other surprising properties.

In this article, I invite readers to learn more about its internal features, many of which became predominant in the market only after the Virtual Boy’s discontinuation.

Display

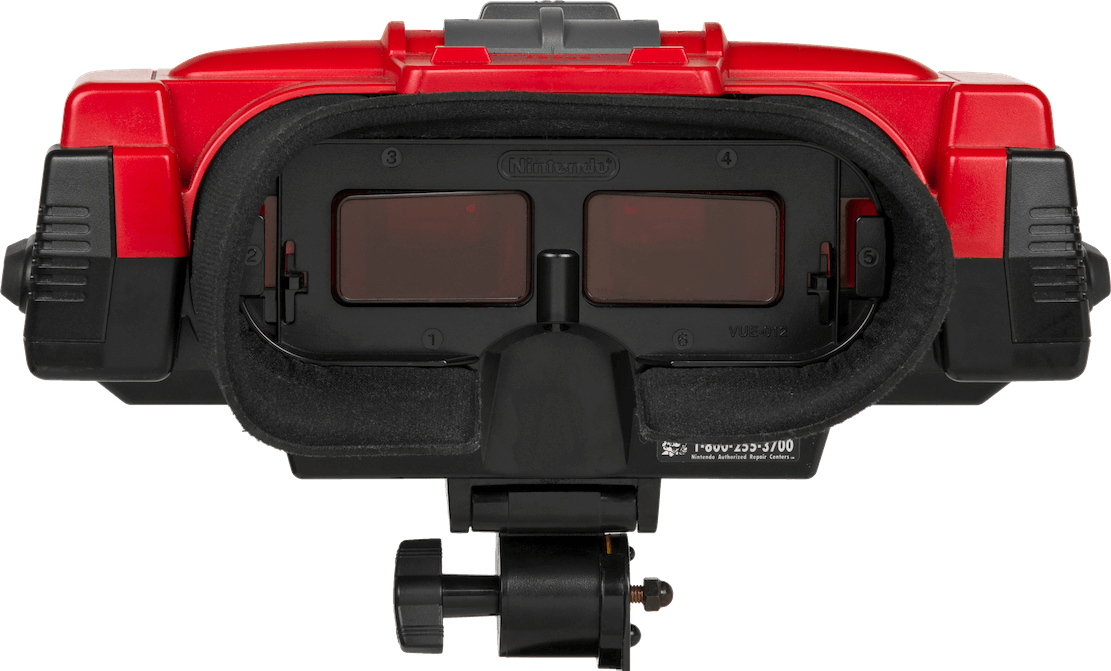

The whole system is a curious piece of engineering. Externally, it resembles a bulky VR headset on a bipod. The player must place their head close to the eyepiece to see the game in action.

Internally, it’s a whole different story (and a very complicated one too). For this reason, I thought it would be better to start by explaining how this console displays images and then go through the internal hardware.

Projecting an image

Once you switch the Virtual Boy on, you will start seeing two monochromatic red pictures (one for each eye) through the eyepiece. So far so good? Well, here is the interesting part: This console doesn’t have a screen, so what you see is more of an ‘illusion’ - Let’s dive deeper to know what’s going on.

The topics involved in explaining this (optics, visual phenomenons, etc) may feel difficult at first, but I constructed some interactive animations to make this section a little more immersive.

Scanner

First switch is the ‘Focus slider’ and below it is the ‘IPD dial’.

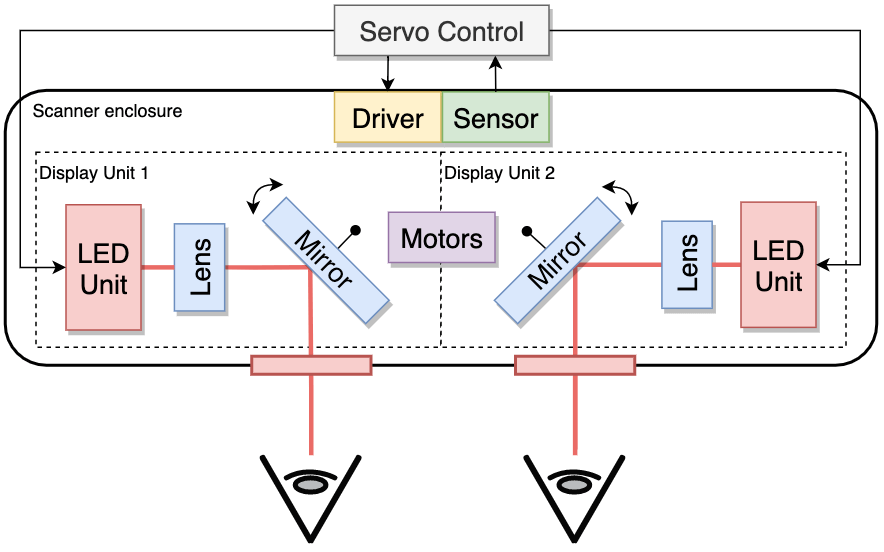

The large volume of this console can be attributed to the Scanner, which fills up a big part of it. The Scanner is the area of the Virtual Boy that displays images. It’s composed of two Display units, each one independently projects a frame (giving a total of two frames, one per eye).

A Display unit is where all the ‘magic’ happens, it’s made of the following components:

- An LED Unit: Contains 224 red LEDs stacked vertically and the necessary circuitry to control each one of them.

- A Lens: Refracts the light coming from the LEDs.

- At the top of the Virtual Boy’s case, there is a Focus slider used to shift the lenses closer or farther away from the LEDs. This allows the user to adapt the console to their focal length (preventing blurry images).

- A Mirror: Reflects the light coming from the lens and directs it to the user’s eyes. Furthermore, this component will be constantly oscillating thanks to a Voice coil motor connected to it. The motor is managed by the Servo control, a separate board that sends electrical pulses at 50 Hz.

- All in all, this is a very complex and fragile area of the console, so there’s a photo interrupter (a type of photosensor) installed. This reports the oscillation observed from the mirror to the Servo control, which in turn monitors the oscillations and applies the necessary corrections.

Next to the focus slider, there is a IPD dial (knob-shaped switch), which adjusts the distance between the two Display units. This is done to adapt the displays to the user’s inter-pupil distance.

Mechanics

| Slower | Faster | |

| Animating at 1x speed | ||

The left and right LEDs are operating (active) during the red and blue periods, respectively.

During the grey period, no LED is operating (idle).

For the sake of simplicity, the angular velocity represented here is constant (but not in the real world).

Now that we have each component identified, let’s take a look at how the Virtual Boy manages to show images to our eyes.

If you haven’t noticed before, there isn’t any dot-matrix display to be found, so why are we seeing two-dimensional images from the eyepiece? Similarly to the functioning of a CRT monitor, Display units play with the way we perceive images:

- The fact the mirrors oscillate enables a single column of LEDs to displace horizontally between our field of view. The angle of the mirror is strategically directed to place the LEDs on 384 different ‘column positions’ distributed across our field of view.

- Human vision is logarithmic and the mirror oscillates at 50 Hz (each period takes 20 ms). This is so fast we end up perceiving 384 columns of LEDs illuminating at the same time (afterimage effect) until the mirror stops oscillating.

- All of this is perfectly synchronised with the LED controller, which updates each LED bulb every time the mirror is slightly moved. Thus, we end up seeing a full picture coming from the eyepiece.

In practice, there are some conditions for all these principles to work:

- The LEDs must only operate when the angular velocity of the mirror is stable (in other words, not when the mirror is changing direction). This can be thought of as the Active State of a CRT monitor.

- In relation to the previous point, the angular velocity of the mirror can’t stay constant (since the mirror can’t change direction instantly, the periods considered ‘stable’ will be subject to forces that will disrupt its velocity). To remedy this, the Virtual Boy stores a list of values in memory called Column Table which instructs how much time to dedicate for each column interval, in an effort to balance out excessive & insufficient periods of ‘LED column’ exposure.

- Let’s not forget that this whole process has to be done twice since we’ve got two display units (one per eye). Unfortunately, both units can’t pull energy and data at the same time, so each one operates at different display periods (out-of-phase, 10ms apart). We don’t notice this (another illusion!).

Display

| Slower | Faster | |

| Animating at 1x speed | ||

Contrary to previous video chips modelled after CRT displays (i.e. PPU and VGP), graphics on the Virtual Boy are not rendered on-the-fly. The graphics chip on this console sends the processed frame to a frame-buffer in memory, each column of the frame is then sent to the LED array for display.

Once the Servo board detects it’s time for display, the graphics chip will start sending columns of pixels from the frame-buffer to those 224 vertically-stacked LEDs, one by one in a strategically synchronised matter so the LEDs will have shown 384 columns during the display period. Hence, the ‘screen resolution’ of this console is 384x224 pixels.

Moreover, we need to store two frame-buffers since each one will go to a different display unit. The graphics subsystem also employs double-buffering and other quirks (mentioned later in the ‘Graphics’ section). So, for now, just remember how a digital frame is sent to the LEDs.

Active periods

| Slower | Faster | |

| Animating at 1x speed | ||

Consequently of this design, there are going to be periods of:

- Active Display during which the LEDs are pulling an image from the frame-buffer and nothing can disrupt it.

- Active Display 2: Same as before but now the other Display unit is operating.

- Drawing idle: A period where none of the LEDs are operating and the angular velocity of the mirror is unstable.

This cycle is repeated 50 times per second (hence the 50 Hz refresh rate). That means that for every frame, the CPU and GPU would have around 10ms worth of time to update the picture that the user will see. In reality, Nintendo’s engineers implemented something more sophisticated. Again, I’ll try to explain this with more depth in the ‘Graphics’ section. But for now, I hope you got a good understanding of how the Virtual Boy cleverly managed to produce a picture with inexpensive hardware.

Some comments

This has been a quick explanation of how optics can turn a single vertical line into a picture. If you own or have read about the Virtual Boy before, you may be wondering when the three-dimensional imagery takes place. I just want to make it clear that none of the previous explanations have a connection with that effect. I’m mentioning this because in the past I’ve seen many places arguing that the oscillating mirrors are the cause of the ‘depth perception’, however, with all the information I’ve gathered in this study, I don’t think that claim is accurate.

That being said, I think it’s time we discuss the 3D phenomenon…

Creating a third-dimensional vision

During the marketing of the Virtual Boy, there was a lot of fanfare regarding the fact this console could project a ‘3D world’. I’m not referring to images with 3D polygons stamped (like the other 5th gen. consoles), but the actual perception of depth.

In a nutshell, the Virtual Boy relies on Stereoscopic images to carry out that illusion [1] [2]. So this system wasn’t only capable of toying with our vision to project a full image, but it also did it in a way we would think certain drawings are closer/far away from others!

The technique is very simple: Each of the two frames displayed (one on each eye) will have some elements slightly shifted horizontally, so when we try to see them with our two eyes, our brain will think they are nearer than others. This depends on the direction the elements are shifted.

Objects shifted towards the centre of your eyes (moved right on the left frame and moved left on the right frame) will appear closer, objects shifted away from the center of your eyes will appear further away. Finally, objects with no shifting will appear between the two other. This approach is called Stereoscopic parallax.

One of the drawbacks of stereoscopy is eyestrain. This was alleviated by the fact games provided an ‘automatic pause’ system which reminded the user to take breaks every 30 min. Nintendo also wrote down various warning messages in their packaging and documentation to prevent serious conditions. In any case, there’s no way to turn 3D off.

CPU

Alrighty, we’re back to actual architecture, let’s see now how games construct the frames and music you see and hear.

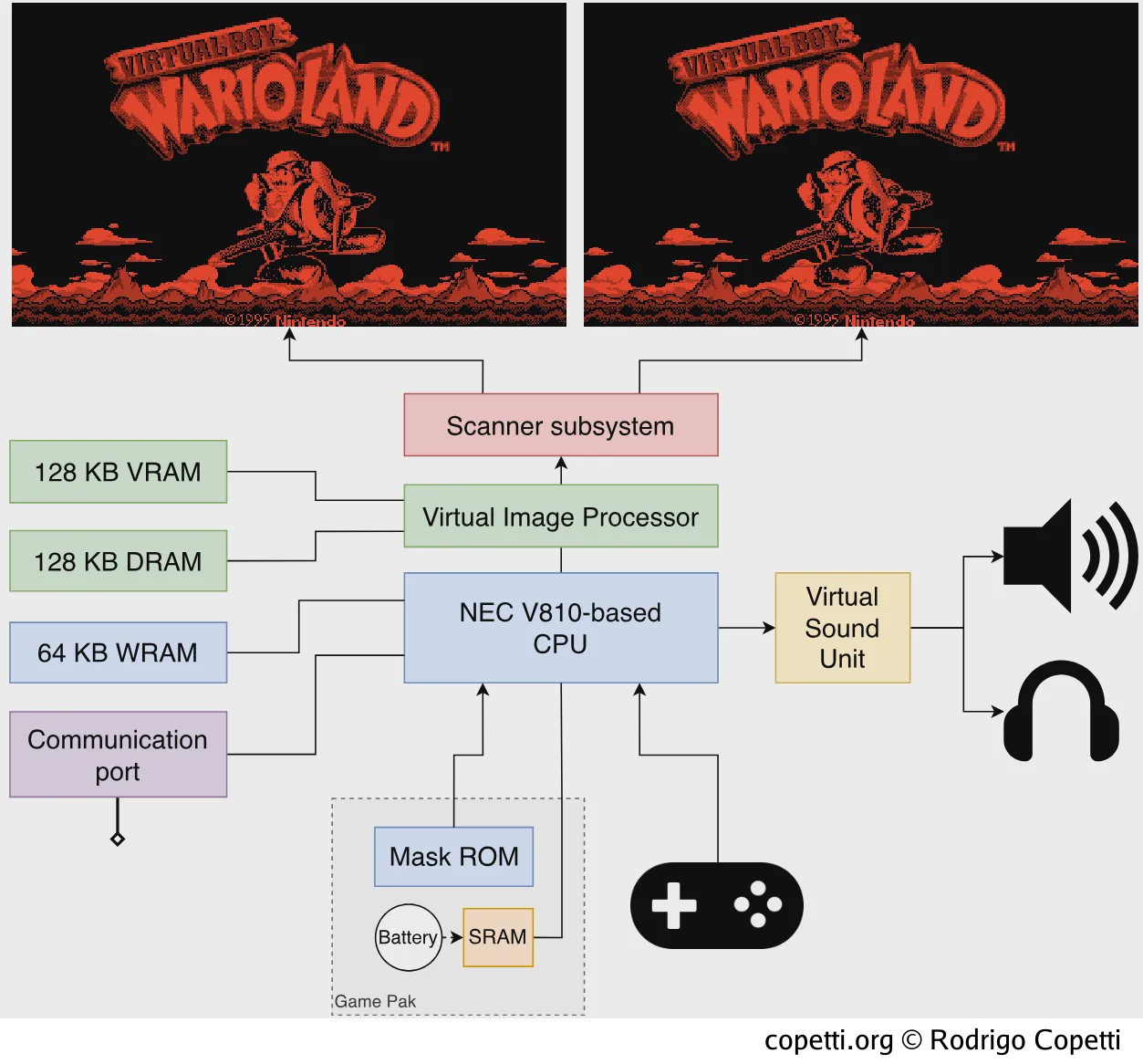

The system uses a customised version of the NEC V810 which operates at an amazing 20 MHz (if the SNES ran at an average 1.79 MHz and the GameBoy ran at 4.19 MHz, I can’t wait to see what can you do with this one!). Nintendo refers to it as NVC because the processor shipped with the Virtual Boy is a combination of a V810 core with some additional components (more details soon).

The V810 is part of the V800 CPU family that NEC designed for the embedded market [3] [4]. While this CPU is not as popular as the competition (i.e. MIPS, 6502, Z80) it does bring a lot of cutting-edge functionality, specifically:

- 32 32-bit registers: This is a complete 32-bit CPU and the registers are well aligned to that.

- V800 series ISA: A RISC instruction set that mixes 16-bit and 32-bit instructions.

- 32-bit address bus: Enabling to access up to 4 GB of memory, an enormous amount of space back then.

- Five-stage pipeline: Here is a previous explanation of instruction pipelining. Worth mentioning that while other systems debuted with three pipeline stages, this one went straight for the five!

- 1 KB L1 Cache for instructions.

- You won’t see any more ‘cached’ portable consoles from Nintendo until the Nintendo DS arrives ~10 years later!

This is very impressive for a portable console in 1995. But if it wasn’t enough, Nintendo added extra resources:

- I/O interfaces: These delegate the task of communicating with proprietary accessories.

- 16-bit external bus: The V810 can be configured either with a 16-bit or a 32-bit bus. Well, Nintendo’s engineers chose the former.

- This will introduce some penalties (wait states) with 32-bit memory transfers, but you’ll soon see why programs won’t be that demanding.

- A Timer: This is just a 16-bit counter.

- A wait control: Stalls the CPU depending on the external bus accessed. This is because the V810 thinks everything comes from the same memory block, but in practice, accessing the Game ROM is slower than, let’s say, internal RAM. So this component corrects the timings.

All of this seems fine and dandy but it does have a big cost: Six AA batteries. This may explain why companies tend to hold on to old tech for portable devices, at least in the 90s.

Memory access

32-bit addresses look very tempting on paper, but if the system won’t use anywhere near 4 GB of memory locations, then it’s a huge waste of resources. For instance, even though the upper address lines never change, they will still be decoded for every memory read.

So, for good reasons, Nintendo cut down to 27-bit addresses. This means that up to 128 MB of memory can be accessed instead. 32-bit words are still used as pointers but the upper 5 bits are discarded. As a result, some parts of the memory map will be mirrored.

That being said, the memory map layout allows the CPU to access the majority of the components that make up this system. This includes [5]:

- 64 KB of RAM (called ‘WRAM’) for general purpose.

- The cartridge ROM and RAM (if included).

- The sound chip.

- The graphics chip, along with its dedicated memory.

- I/O and their respective registers.

This is as far as the CPU goes, now it’s time to see what can you do with it!

Graphics

Let’s recap the requirements for the proper display of graphics:

- The Virtual Boy must show two frames.

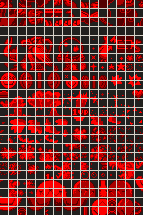

- Each frame has a resolution of 384x224 pixels.

- The colour palette is composed of various shades of red, plus black (when the LED is off).

- The scenery requires parallax applied.

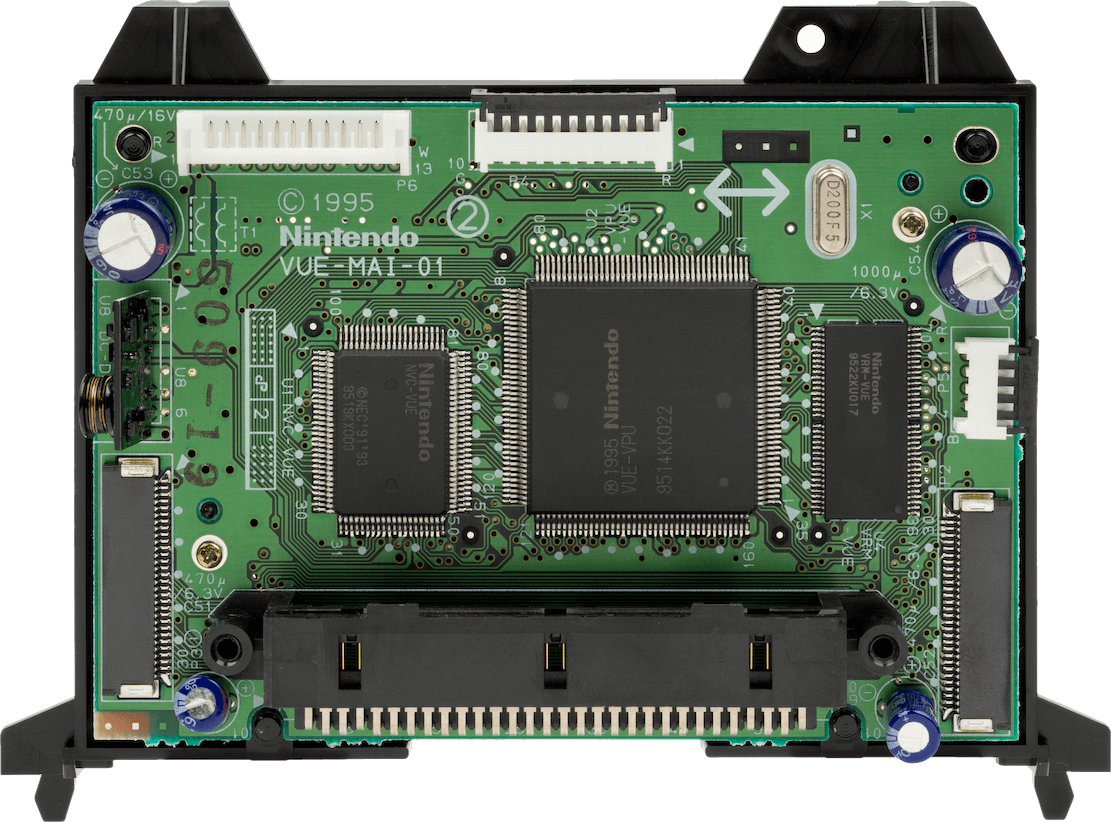

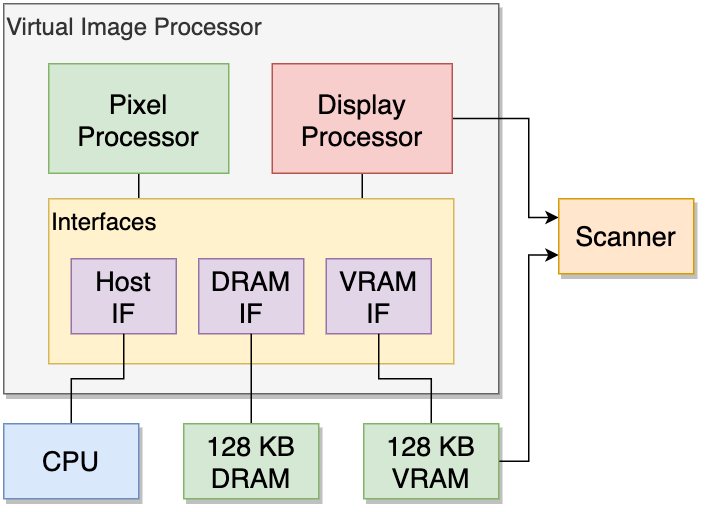

Good news is that all of this is accelerated by the Video Image Processor or ‘VIP’, a dedicated chip made by Nintendo. It has some features inherited from the old PPU but I consider it a clean break from its predecessors.

Architecture

The VIP may seem like another tile engine at first, but it’s much more advanced than that. For starters, it not only processes graphics data but also controls the Scanner.

Moreover, while classic tile engines rendered graphics per scan-line, the VIP relies on a frame-buffer architecture, where the final frame is stored in memory as a bitmap and then sent for display. This is closer to the modus operandi of modern 3D renderers. In fact, the Virtual Boy took a step further by using some sort of page flipping, where two frame-buffers are stored per Display unit and the scanner picks up one while the VIP is writing over the other. All of this helps to prevent image tearing.

Having said that, you can divide the VIP into three main areas:

- The Pixel Processor or ‘XP’: Generates backgrounds and sprites, much like the PPU. It sends the final processed bitmap to the frame-buffer area in memory.

- The Display Processor or ‘DP’: Controls the Scanner and sends a frame-buffer for display.

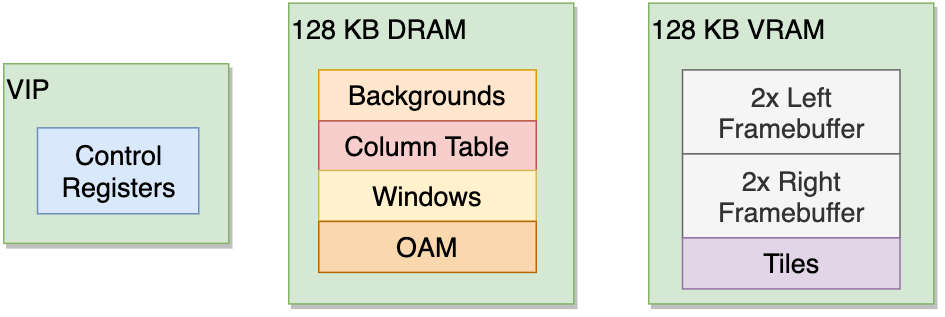

- The Interfaces: Provide access to two blocks of memory: 128 KB of VRAM and 128 KB of DRAM [6]. They also arbitrate access between VRAM and the CPU (called ‘Host’ from the VIP side).

Overall, the pipeline is very simple:

- The CPU sets up the VIP by writing over its internal registers and filling up VRAM and DRAM with the required materials.

- The XP will then generate frame-buffers that will be stored in VRAM.

- The DP selects the necessary frame-buffer and sends it to the Scanner for display. This is done by copying the frame, four columns at a time, to a small buffer area in VRAM called Serial Access Memory or ‘SAM’, which is automatically broadcast to the Scanner.

Organising the content

From the developer side, there are two blocks of memory used by the XP and DP:

- 128 KB of DRAM for storing graphics data that will be processed.

- 128 KB of VRAM for storing the frame-buffers that the DP will look for.

- Because we have two Display Units, we need a total of four frame-buffers. Each bitmap generated is 24 KB wide, so we’ll need to allocate 96 KB of memory. The remaining 32 KB is used by the XP for storing tiles.

Notice that this VRAM is ‘real’ dual-ported DRAM [7], not just a block of RAM reserved for graphics (which Nintendo also calls ‘VRAM’). Dual-ported DRAM enables two devices to read from it at the same time, which explains why the XP can write over VRAM while the Scanner is reading from it concurrently.

Additionally, Nintendo uses a VRAM chip nowhere to be found in the off-the-shelf catalogue. There isn’t a lot of documentation about it, but from the information described in the patent application, SAM may be stored in a separate area inside this chip. This area is presumably made of SRAM instead and contains extra circuitry to allow the Scanner to pull 16 bits at a time [8].

Constructing a frame

Let’s dive deeper and see now how a single frame is drawn on the Pixel Processor. For that, I’ll borrow the assets of ‘Virtual Boy Wario Land’. I strongly recommend reading about a previous tile engine to make explanations easier.

Tiles

We have previously seen how traditional tile engines build their layers using 8x8 bitmaps. In the case of the Virtual Boy, tiles (originally called ‘Characters’) are stored in VRAM in an area called Pattern table. Each tile declared occupies 2 bytes, so there is enough space for 2048 of them.

In terms of colours, developers can construct eight colour palettes, four for Background graphics and another four for Sprites.

One may wonder what’s the point of colour palettes if the LEDs are monochrome. Well, this enables developers to use different shades of red. These shades are obtained by altering the brightness of the LEDs. The brightness settings are stored in two registers, which then you reference in the palettes to catalogue the different shades. The resulting palette will contain your two custom reds, plus another red automatically calculated from the sum of both, and finally, the ‘transparent’ colour.

Backgrounds

This one is mostly hidden during gameplay, and then shown completely after hitting pause.

The background layer is very simple, pick tiles to form a 512x512 map (64x64 tiles, 4096 tiles in total). Now, it doesn’t end here, because instead of having just a single background layer available… We have 14!

Each individual background layer is called a Segment. A single Segment fits in 8 KB of memory, where each tile reference contains H/V flip attributes and palette index. Each tile reference occupies 2 bytes of memory.

The Pixel Processor also allows to combine different segments to generate a bigger layer, but only a set of combinations is available. The largest mix combines eight segments.

Sprites

Sprites (or ‘Objects’, as Nintendo calls them) are single tiles with independent coordinates but occupy more memory.

There is a place in DRAM called OAM with 8 KB of memory allocated, here is where sprites are defined. Each sprite definition occupies 8 bytes, so up to 1024 sprites can be declared.

Each sprite has the following properties available:

- X and Y coordinates.

- A flag that decides whether to display it on the left screen, the right one, or both.

- The Parallax offset, allowing to apply an automatic parallax: Each screen will display the sprite with a slight horizontal shift.

- This value is signed: If the value is positive then it will make it look far away. On the contrary, if the offset is negative it will make it look closer.

- The index of the tile used.

- H/V flip.

- The palette index.

You’ll also notice there are no screenshots shown for this explanation, the next block explains why.

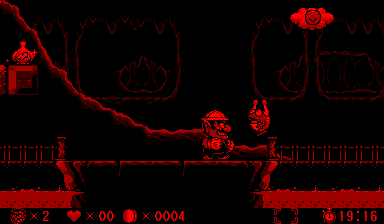

Window

This one is rendered on both displays.

This one is expanded when you pause the game.

This is the ‘sprite layer’ I owe you from before.

Some are meant to be rendered on both displays (using shifting effects), while others are exclusive to one.

The layering system may seem simple at first, after all, the VIP provides ‘Background’ layers and a ‘Sprite’ layer. So, what else do we need?

The fact is, to display any of the previous layers mentioned, we have to place them in a ‘bucket’ called Window (also named ‘World’). A Window is the actual plane that will be rendered to the screen, it is filled with layers previously constructed. There are 32 Windows available which will overlap to form the final frame, each Window declaration occupies 32 bytes.

Windows provide different rendering modes. You can grab a Background or Sprite layer and display it as it is. For that, the Window has to be set to Normal mode and Object mode, depending on which type of layer you are using. However, you can also take advantage of additional modes which apply extra effects on background layers:

- Line Shift Mode: Individual rows of pixels can be shifted horizontally. This resembles the good ol’ effects applied during horizontal interrupts.

- Affine Mode: As the name indicates, you get to apply affine transformations! (scaling and rotation or combined to form perspective projection [9]).

Result

After setting everything up, the Pixel Processor will start rendering the 32 Windows. Once it’s done, the final frame will be placed in the frame-buffer area. This process is repeated for the other Display unit as well.

Since the system employs a double-buffered design, the Display Processor will always fetch the frame-buffer that the Pixel processor is not manipulating, which greatly avoids tearing. On the next active period, the Pixel Processor will overwrite the frame that the DP previously displayed, and so on.

If there isn’t much to render (i.e. few Windows are used), there will be long gaps between writing over the frame-buffer and the DP picking it up. This allows the CPU to make extra changes over the frame if it wants. The VIP is also prepared for this: The CPU can set up interrupts to check various states of the VIP, including this case.

On the other side, if there are too many affine Windows to render (for instance) the XP may ‘miss the deadline’ which will cause frame drops. Luckily, there are interrupts available to detect that too. In any case, the official docs provide timings each type of layer can take.

Creative content

As you can see, there is a lot more technology in this console than meets the eye.

At first, I thought the Game Boy Advance was the first portable console that could reconstruct the acclaimed Mode 7 of the Super Nintendo, almost 11 years later. It turns out it was the Virtual Boy all along, five years later. But even so, we’ve seen before that affine transformations in the Virtual Boy could be applied to each of the 32 layers (although with some limitations).

Furthermore, all these new functions worked alongside the Parallax effects, something that the VIP also took care of.

I wonder what kind of games we would’ve seen if this console had lasted a little bit more, just enough so developers could get more comfortable with this hardware.

Another interesting feature was that by allowing the CPU to alter the frame-buffer, it provided developers with the ability to construct their own renderer if the VIP wasn’t enough for them. This is what some games relied on to present their innovative graphics. For instance, ‘Red Alarm’ implemented a scenery constructed with polygons rendered by the CPU.

Unfortunately, fundamental issues like visible surface determination weren’t always addressed properly, I’m not sure if that was due to the limitations of the CPU. In any case, this resulted in a scene turned into a messy mesh instead, which made it difficult for the player to distinguish which objects were behind others.

Audio

Imagine you grab the Game Boy’s Wave channel, multiply it by five and add a noise channel: That’s pretty much the offering of the Virtual Boy’s sound chip. You can also think of it as a sibling of the PC Engine’s.

In the motherboard there’s another chip called Virtual Sound Unit or ‘VSU’ that provides the sound capabilities. The PSG relies on internal RAM to store five wavetables and a register file to configure each of the six channels available. Registers are 8-bit wide while the internal RAM is connected to a 6-bit data bus (the CPU will still treat 6-bit words as a single byte, but the upper two bits are discarded).

Each wave is made of 32 PCM samples (encoded in 6-bit values). Channels have a panning control setting (with a volume level from 0 to 15 for each left and right) and an 11-bit frequency control.

There’s also a basic envelope control for each channel that makes the volume grow or decay over time. The fifth channel supports more effects, namely a sweeping function to progressively shift the frequency and a modulator to alter the waveform based on some values stored in the internal RAM.

The sixth/last channel can only output noise.

Output

The mixed result is stereo with a resolution of 10-bit and a sampling rate of 41.7 kHz. It’s also worth pointing out that the console has stereo speakers, so you don’t have to wear headphones to be able to enjoy this!

I/O

This is in theory a ‘portable’ console, so don’t expect game-changing accessories (pun intended). There’s still some interesting stuff though.

Available interfaces

Internally, every component is pretty much directly connected to the CPU, except some areas handled by the VIP exclusively.

Externally, there are two connectors available for accessories:

- The Serial Port: Connects the controller. Data transfer is performed in a serial manner (1 bit at a time) [11], but the interface adapts it to return a 16-bit value for the CPU to read (each bit place signifies a button pressed). Interrupts can also be set up to notify the CPU the instant any key is pressed.

- One pin of this connector also sends 5 Volts from the controller to the console. This is actually used to power the console!

- The Communications Port: Whilst not an accessory per se, this port is used to talk to another Virtual Boy. This reminds me of the Link cable that the Game Boy uses. The two Virtual Boys communicate in a master-slave manner using serial data streams.

- This really makes you wonder what kind of multiplayer functionality was Nintendo envisioning. Unfortunately, no game ended up using this feature.

The provider

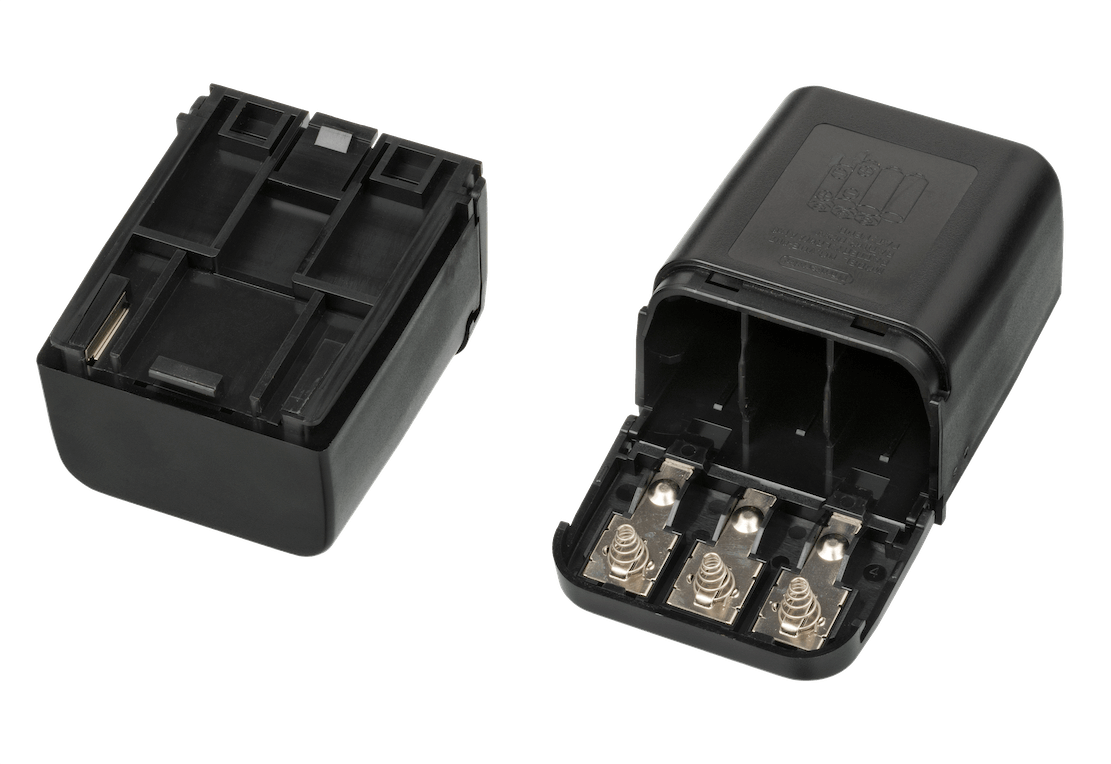

The controller of the Virtual Boy is very peculiar compared to the rest of the console line. Somewhat similar to the Super Nintendo one, without the ‘X’ & ‘Y’ buttons, a larger handler and an extra D-Pad on the right. On top of all this, you can’t look at it while playing.

Also, because the controller is also supposed to supply power, it comes with a removable battery magazine on the back. The cartridge is called Tap and fits six AA batteries. If users got fed up with looking for batteries after any of the six wears out, they could also buy a different tap that connects to an external power supply.

In the case of using the latter accessory, playing with everything interconnected with cables may feel like a house of cards (especially if you can’t look at it during gameplay) but I guess that’s the price to pay if you don’t want to worry about batteries 🙂.

Operating System

The V810 starts execution at address 0xFFFFFFF0H. That means that when the Virtual Boy is switched on, it will look for instructions from that address. That being said, that location is found on the cartridge ROM. This means that the game has the upper hand in the initialisation of the hardware.

Also, there isn’t any BIOS chip to be found on the motherboard, so there won’t be any operating system or any abstraction layer to help simplify operations.

House chores

For this reason, Nintendo instructed developers to perform several chores to ensure the proper functioning of this console, these include:

- WRAM is usable only after 200 microseconds (0.0002 seconds) since the console’s startup, so the docs contain a list of steps that games must follow to wait for this.

- The game must fill the Column table. To recall previous explanations, the ‘active display’ period has a variable angular velocity. To prevent some columns of the frame from being narrower than others, games fill up a table in DRAM that provides corrections. To make things easier, Nintendo provided a default Column table in their SDK that games could use.

- The table can also be amended at any time during gameplay, and because it consequently controls the amount of LED emission, the table also serves as a mechanism for adjusting the amount of brightness per column.

Games

One may think that game development would just inherit the same facilities of the Game Boy (that is, stick with assembly), but it turns out Nintendo and NEC invested a lot of new technology to speed up/modernise this area.

Development ecosystem

Game studios had the option to purchase a development kit from Nintendo which included a fully-equipped debugging station, a toolchain and plenty of documentation.

The hardware kit was called VUE Development System (‘VUE’ was the codename of this console), it was a PC-like tower that contained the Virtual Boy’s internals plus 4 MB of RAM (expandable to 8 MB!). It is connected to a headset (with the same shape as the retail Virtual Boy) and a retail controller. To run and debug programs, the dev kit contained an interface board that talked to an IBM PC using SCSI. To use the equipment, you needed an IBM PC/AT (or clone) with an Intel 80386, 2 MB of Memory and MS-DOS installed.

The software kit consisted of a linker, assembler and debugger. At request, Nintendo also offered a C compiler. That means it was no longer needed to write programs directly in assembly! All in all, this setup took 1.5 MB of your precious -and noisy- hard disk.

It’s too bad that this model of development was eventually reverted with the release of the Game Boy Colour. I’m guessing that this was because the Game Boy’s CPU can’t handle ‘unoptimised’ code from a compiler.

Medium

Game cartridges are called Game Paks. They have the same name as the Game Boy medium but they are completely different in terms of shape and functionality.

Due to the memory address space, the ROM can be up to 16 MB without a mapper. This applies to external RAM too (up to 16 MB). Just like the Game Boy, they can have battery-packed SRAM. The cartridge is accessed using a 16-bit data bus.

Come to think of it, 16 MB of ROM is quite a lot for the mid-90s. After all, the max size of a GB ROM was 128 KB! (without a mapper). On the other side, let’s not forget this console uses 32-bit addresses, so every pointer is 4 bytes long. This is two times the size of Game Boy’s addresses (2 bytes), so it adds up to the space requirements.

Rules

Due to safety concerns, Nintendo ordered developers to include a couple of images to mitigate eyestrain and other conditions that may arise from excessive screen time.

Games have to include a ‘read the instructions’ warning, an alignment guide and an automatic pause dialog.

These screens will appear after the console is switched on. The first one ‘orders’ the user to read the instructions manual before continuing.

The second one was some sort of a ‘test card’ that was used to properly adjust the IPD dial and the focus slider.

The third one asked the user if they would like to be reminded to take a break every thirty minutes.

The first and third screens were often customised to fit the game’s theme.

I don’t think Nintendo dictated rules like this anymore until the release of the Wii.

Anti-Piracy and Homebrew

The fact that Nintendo created yet another variation of the Game Pak allowed them to retain control of distribution. Although, since this console never took off, bootleggers probably didn’t even bother.

Apart from that, there are no copy protection or region-locking mechanisms implemented in this console. Games imported from America and Japan will work on either console. Also, assuming someone would be willing to manufacture their own Game Paks, Homebrew is also possible.

The last time I checked, Flash carts were theoretically possible but only two reached commercialisation, the ‘FlashBoy Plus’ and the ‘Hyperflash32’ (I’m not on commission! but I thought it’s worth the mention).

That’s all folks

The only remaining member of the user research team 😉.

Throughout this series, we’ve seen all kinds of systems, some with limited CPU but impressive synergies, others with questionable hardware but beautifully packaged. This case, however, was an interesting proposal: The CPU wasn’t certainly limited and the graphics were up to the task. The sound wasn’t exceptional, yet remained similar to the rest of the portable consoles in the market.

So, why didn’t many children play with it? I’m afraid a marketing study goes beyond the scope of this article. But from the technical side, I think the message just didn’t get through: At the end of the day, nobody cares for affine transformations or a pipelined CPU if you can only see red dots.

I guess that was my main motivation for writing this article, to prove somehow that innovative technology can be everywhere, even where we least expect it.

I’d also like to thank the Planet Virtual Boy community for helping me with the study. They are currently working on many projects that give new life to the Virtual Boy, so I recommend checking out their forum for more info.

Finally, this has been the last article of the ‘retro saga’, the next one will return to (relatively) modern renderers, starting with the PSP!

Until next time!

Rodrigo